One of my favorite film genres is the holiday adjacent film. The defining features of this category include the celebration of a holiday within the plot (can be a vital crux or not) and celebratory signifiers featured in a selection of scenes. For example, most people probably do not watch Stanley Kubrick’s last film, the psychological drama Eyes Wide Shut around Chirtsmas each year because the plot is set during the holidays; however, it is a Chritsmas movie to me! (Yes, I will be writing about this in the coming weeks.) Ladybird, the 2017 coming-of-age film by Greta Gerwig, is a Thanksgiving movie. Full stop. Every year after watching the Macy’s Thanksgiving parade, I fill a plate with turkey, roasted vegetables, mash potatoes, stuffing and a heaping dollop of cranberry sauce to accompany my yearly viewing.

Our story begins in the fall of 2002, Christine “Ladybird” McPherson and her mother driving along listening to a book on tape (remember those) of John Stienbeck’ s classic The Grapes of Wrath as they wind their way throughout Northern California, touring colleges Ladybird might attend next year. As soon as Ladybird reaches for the radio to turn on music to avoid a moment of silence with her mother, an argument ensues where she pleads how badly she wants to live where culture happens and she is met with a counterpoint that her current grades are a foil to her dreams. To have the final word in the squabble, Ladybird hurls herself out of the car.

Then, a quick cut to a school church service, a place where I have been many times in my life. This is the only movie I’ve watched where I have felt parts of my life reflected back to me. Ladybird and and her partner in crime Julie remind me of my friends and I in middle school. We were far from being the popular girls, but we managed to navigate the strict unspoken social and extremely loud religious rules imposed upon us. We would spend our lunch time in the art room playing with instruments, going online, and trying to decipher if our crushes liked us back (you would think we were training to be body language experts if you heard us analyzing a shoulder brush or a glance). One of my favorite scenes in film history is of Ladybird and Julie laying on their backs discussing their personal adventures in self pleasure while snacking on unconsecrated communion wafers.

Ladybird and Julie join the school theater program, primarily as a way for Ladybird to have something notable in her transcript to offset her poor academic performance. During auditions, she quickly falls for Danny, a tall drink of Irish Catholic holy water whose grandmother lives in the large blue dream house her and Julie lust after on their walk home from school. A key point of tension is when Ladybird’s mother is upset that she is choosing to spend her last Thanksgiving before college at a stranger’s home instead of with her family. To make matters more complicated, the budding relationship ends as soon as it starts after Ladybird catches canoodling with another boy in the bathroom during the school play’s opening night after party.

I’m not going to go into detail about Timmy Chalamet’s role in the film because he plays a guy who is truly a dime a dozen. Talking about yet another “cool guy” who acts like they are more interesting than they really are is a waste of time, this genre of person is the human equivalent of a snooze.

Ladybird is a dreamer, much like myself when I was younger and living in a city that stunted my growth. Not only is her current location restricting her dreams, but her family’s finances make materializing her future plans harder. Her mother works as a psychiatric nurse (double shifting to make ends meet) and her father was recently laid off. However, her sweet father assists Ladybird with the application fees to her aspirational East Coast schools (to appease her mother she applied to schools in the UC system and sadly to her she got into Davis). After tearing through her letters of rejection, she is waitlisted for an unnamed school and soon packs her bags to head East.

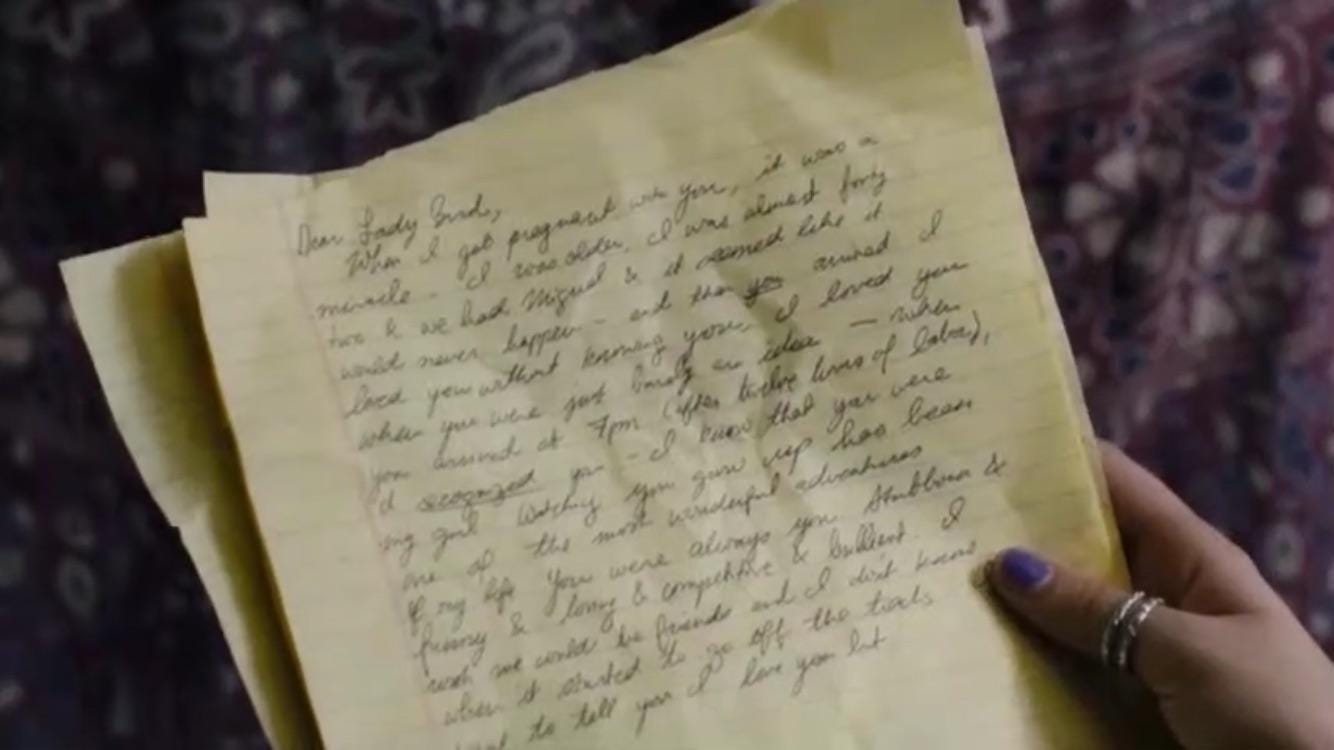

It is not explicitly stated, but Ladybird definitely ends up going to NYU. Her dramatic antics are key tells of a Tish student (as is the scene of her getting off at the West 4th/Washington Square station). As soon as she’s settled in her dorm, she discovers the cast off notes her mother tried writing for her that her father slyly slipped into her suitcase before leaving for her new life. Later, she’s at a college party where her past comes back to comfort her. A fellow reveler asks her her name and for the first time we hear her claim her birth name, the city of Sacramento and her faith proudly. The most rebellious act to do in New York is to be yourself without pretense or succumbing to the clutches of clout chasing. No one at her university is like her and that’s exactly how she got accepted in the first place. As her night of revelry goes south, she lands herself in the hospital after attempting to numb the monotonous party babel with alcohol. In the end, she finds her way back to what she rejected yet what kept her grounded throughout her life: the church and her mother. After attending a Sunday service, she calls her mother to say thank you.

A relationship to faith and parent/child connections are perpetually complicated. The ebbs and flow of life lead us through passages and around coroners where connections are lost and, at times, irreparably damaged. Looking in the mirror, realizing the foundation for which we were built is cracked allows us to mix up spackle repair the damage on our own terms. Scars are markers of lessons learned, time heals our wounds eventually.